Why is this patient feeling faint?

Articles in this section are inspired by, but not based on, real cases to illustrate the importance of knowledge about ECGs in relation to clinical situations in general practice. Management is not discussed in detail.

Mohammed is a 74-year-old man who comes to see you because he sometimes feels faint when he stands up and goes to walk. The feeling continues for several minutes after he starts walking and improves but does not go away completely when he sits down again. His energy levels have not been normal during the past few weeks and the faintness has occurred intermittently on most days, but not every day. He says he could pass out but has never actually done so. He has had no shortness of breath or chest discomfort.

Mohammed takes ramipril 5 mg in the morning for hypertension and atorvastatin 40 mg and fenofibrate 145 mg daily for hyperlipidaemia. He had been investigated by a cardiologist five years ago for atypical chest pain and had been diagnosed with mild coronary artery atherosclerosis. This has been medically managed. He has impaired glucose tolerance (glycated haemoglobin level 6.1%) and is an ex-smoker (he stopped smoking five years ago). He does not consume alcohol and has no other medical problems. He has recently lost about 8 kg by exercising during the past two warmer months.

Q1. What are the differential diagnoses of Mohammed’s symptoms?

Mohammed could have postural hypotension. His blood pressure medication may be too high a dose for him now that he has lost weight and this may also be the case in hot weather (when he may be intermittently vasodilated or mildly dehydrated). Mohammed could have an irregular heart rhythm causing his symptoms, such as tachyarrhythmia or bradyarrhythmia. Other differential diagnoses include significant valvular heart disease or heart failure.

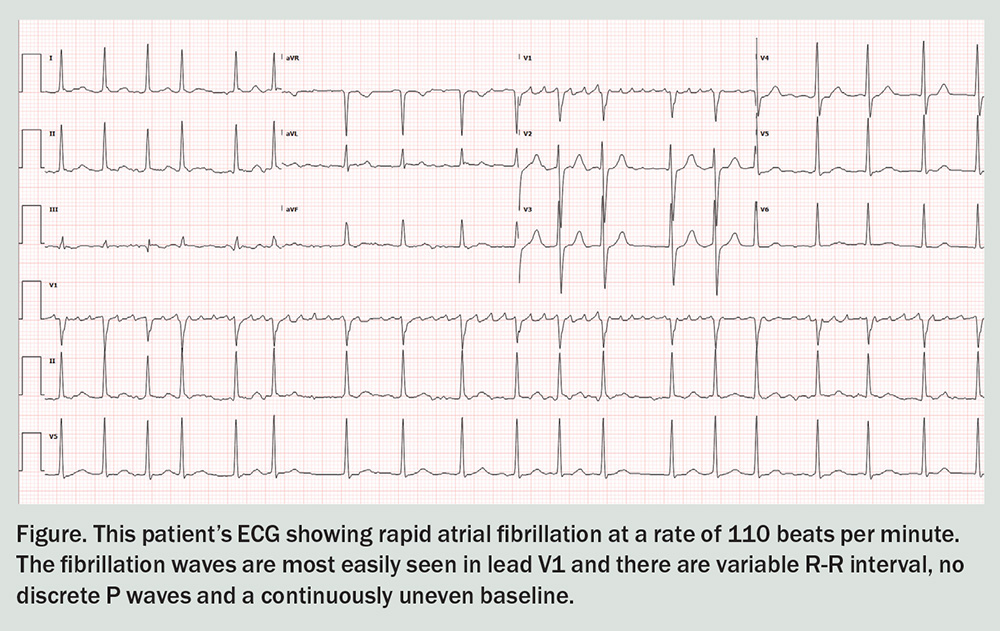

Mohammed’s oxygen saturation level is 97%, and his blood pressure is 130/80 mmHg sitting and 125/76 mmHg standing. His heart rate is 55 beats per minute, as measured by using a sphygmomanometer, but is 38 beats per minute when his pulse rate is measured at the wrist straight after. Mohammed feels tired but is not feeling faint during the consultation. You prioritise an ECG and this is performed promptly (see Figure).

Q2. What does the ECG show?

This ECG shows rapid atrial fibrillation at a rate of 110 beats per minute. Note the fibrillation waves are most easily seen in lead V1, as is usually the case. The ECG features include a variable R-R interval, no discrete P waves and a continuously uneven baseline. There are no ischaemic changes present.

Q3. Why does Mohammed have a pulse rate of 38 beats per minute just after the sphygmomanometer registers a heart rate of 55 beats per minute and his ECG shows a rate of 110 beats per minute?

Rapid atrial fibrillation may cause intermittent beats to be of a volume too low to feel clinically at the wrist. It should be audible at the apex on auscultation as rapid atrial fibrillation. Cardiac auscultation and examination should be carried out at some point during the consultation as he could have mild cardiac failure or have a significant heart murmur.

Q4. What are the physiological causes and ECG features of atrial fibrillation?

In atrial fibrillation, there is abnormal automatic focus of cells within the atria locally at the base of the pulmonary veins or multiple re-entrant wavelets within the myocardium that create the electrophysiological dysfunction. This may be combined with a shortened atrial refractory period and delayed intra-atrial conduction, producing sustained atrial fibrillation from the irregular conduction of electrical impulses.

The atria contract irregularly and so the R-R interval is variable, the P waves are absent and the baseline undulates. The ventricular response is variable and may be slow (slow AF), normal or fast (rapid AF). Abnormal automaticity in the pulmonary veins is more likely to produce paroxysms of atrial fibrillation that stop spontaneously. Multi-wavelet re-entry within stretched or scarred atrial myocardium is more likely to produce persistent atrial fibrillation.

Q5. What are the medical causes of atrial fibrillation?

The medical risk factors of atrial fibrillation include hypertension, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, left-sided valvular heart disease, obesity, chronic obstructive airway disease and sleep apnoea. It is also common in the days to weeks after open cardiac surgery, especially coronary artery bypass and aortic and mitral valvular surgery. Less common risk factors include excess alcohol consumption and high endurance training.1

Men may be at an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (more studies have been done in men than women) and there is a significant genetic association. There is a two-fold lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation if a first-degree family member has atrial fibrillation.1

Atrial fibrillation is increasingly common with age, partly because the risk factors mentioned above are more prevalent in later life. Many of these medical conditions are associated with chronic inflammation, metabolic changes, increased atrial pressure and volume overload, diastolic dysfunction and chronic inflammation. This results in gradual fibrosis of the myocardial and neural cells and the increased risk of atrial fibrillation.1 An estimated 5% of the Australian population aged 55 years and older have atrial fibrillation.2

An early rhythm control strategy (using some or all of: antiarrhythmic medication, cardioversion and catheter ablation) has been shown to produce improved outcomes compared with early acceptance of atrial fibrillation with treatment limited to rate control and anticoagulation.

Aggressive treatment of sleep apnoea, obesity and hypertension are important parts of treatment.

Outcome

Mohammed was stabilised in hospital initially with intravenous sotalol and then oral sotalol, and he was anticoagulated with apixaban 5 mg twice daily.Ramipril was ceased. His cardiac auscultation was normal, and chest examination and chest x-ray showed that he did not have cardiac failure. His serial troponin levels, thyroid function, iron study findings and routine blood test results were all normal. He reverted to sinus rhythm overnight and was discharged the next morning with instructions to return to his GP in the next few days for referral to a cardiologist.

A resting cardiac echocardiography was performed in advance of the cardiology review, which showed an ejection fraction of 60% and mild to moderate left atrial enlargement (he did not have atrial fibrillation). His stress echocardiography was normal (terminated due to fatigue at 8 minutes). His CT coronary angiogram suggested persistence of mild atherosclerosis and so he has been advised to continue on medical management for this. CT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Wasmer K, Eckardt L, Breithardt G. Predisposing factors for atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Geriatr Cardiol 2017; 14: 179-184.

2. Australian Government Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Atrial fibrillation in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2020. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/atrial-fibrillation-in-australia/contents/how-many-australians-have-atrial-fibrillation (accessed October 2024).