Atrial flutter in a 65-year-old woman with asthma

Articles in this section are inspired by, but not based on, real cases to illustrate the importance of knowledge about ECGs in relation to clinical situations in general practice. Management is not discussed in detail.

- The normal atrial flutter rate is 250 to 320 bpm, usually 300 bpm, although it may be slower than this in patients on antiarrhythmic medications.

- The AV node is not normally capable of conducting at this rate, so there is usually a 2:1 block or greater.

- Typically, there are sawtooth flutter (F) waves on the ECG that are best seen in leads II, III, aVF and V1.

- Elective electrophysiological study and catheter ablation of the re-entry circuit are an option as first-line management for appropriate patients who have atrial flutter.

- Radiofrequency catheter ablation is superior to medication for controlling rhythm and rate and has a low incidence of side effects and complications.

- Medications used for control of atrial flutter rate and/or rhythm include beta blockers, sotalol, diltiazem, verapamil, digoxin, flecainide and amiodarone.

- Flecainide should not be used without concomitant AV nodal blocking drugs such as beta blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium antagonists as it may cause 1:1 conduction and cardiovascular collapse.

- Re-anticoagulation, the patient’s risk of thromboembolism should be weighed against their bleeding risk.

The second time Jade was rushing to an appointment and returned home as she had forgotten something. While she was there she had the same symptoms, but this time they lasted an hour. She has had no chest pain, but felt a bit short of breath (but not like her asthma symptoms). She lay down for 20 minutes and got up to go to the bathroom as she felt the urge to open her bowels.

Jade is meant to take fluticasone/salmeterol 250/25 mcg, two puffs twice daily, but often omits this until she is symptomatic. She has recently restarted this. She takes escitalopram 10 mg daily, and her anxiety and mild depression are well controlled. Jade sees her GP the day after the second event. The GP says she is disappointed Jade did not call 000 during the palpitations, given that they lasted an hour. Her examination, especially the respiratory and cardiovascular system, is now normal.

Q1. What are the differential diagnoses?

Atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, supraventricular tachycardia, sinus tachycardia (either ‘inappropriate’ or secondary to other illness such as anaemia, infection, pulmonary embolus, congestive heart failure), atrial tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia.

Q2. What first-line investigations should Jade’s GP arrange?

A resting ECG and a 24-hour Holter monitor; a full blood count; iron studies; measurement of levels of serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine, thyroid-stimulating hormone, fasting cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, fasting blood glucose and C-reactive protein; urine dipstick and, if abnormal, culture.

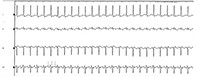

Q3. Jade’s ECG and blood tests are normal. What does this section of her Holter monitor strip (Figure) show?

This Holter monitor shows a narrow-QRS tachycardia, rate 155 bpm with flutter waves, consistent with atrial flutter with a 2:1 block. Jade did not record any symptoms but she recalls she was busy tidying the house at that time.

Q4. What would the ECG show during an episode of this arrhythmia?

The normal atrial flutter rate is 250 to 320 bpm, usually 300 bpm, although it may be slower than this in patients on antiarrhythmic medications. The AV node is not normally capable of conducting at this rate, so there is usually a 2:1 block or greater. Typically, there are sawtooth flutter (F) waves that are best seen in leads II, III, aVF and V1. Flutter waves with a 2:1 block may mimic myocardial ischaemia due to ST complex distortion.

Variable block may sometimes occur giving an irregular ventricular response. Occasionally the rate may turn into a 1:1 conduction, in which case the rate is so fast that cardio-

vascular collapse may occur (especially in patients who have underlying heart conditions or Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome). This can also be seen in patients receiving flecainide and for this reason, this drug should not be used without concomitant AV nodal blocking drugs like βbeta blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium antagonists.

Q5. What should Jade’s doctor do next and what instructions should Jade be given?

Jade needs to have transthoracic cardiac echocardiography (to exclude valvular disease, an early cardiomyopathy and atrial thrombus) and a consultation with a cardiologist. She should be instructed not to drive during any palpitations, and to sit or lie down and call 000 if they happen again. Jade should avoid coffee, energy drinks, alcohol and, if possible, stressful situations.

Q6. Should Jade continue her asthma medication?

Yes, as uncontrolled asthma could be a more serious condition if the palpitations recur and hypoxia may precipitate atrial flutter. However, she should be told to use the lowest dose that controls her asthma and to take it regularly, so she has no need for extra doses or reliever medication. It would be reasonable to change her to preventer alone, for example fluticasone 250 mcg three puffs twice daily as a trial of asthma control without salmeterol, and to use salbutamol or another reliever only if needed.

Q7. Jade wants to know what management the cardiologist might suggest.

Electrophysiological study and catheter ablation of the re-entry circuit are an option as first-line management for appropriate patients who have atrial flutter. This is because radiofrequency catheter ablation is superior to medication for controlling rhythm and rate and has a low incidence of side effects and complications. Usually these are performed as an elective procedure. Typically, most patients with atrial flutter will have a good response to ablation and may not need long-term medication or anticoagulation. For atrial fibrillation, the considerations are different, as ablation for atrial fibrillation has higher complication rates and lower risks, and is only appropriate for selected patients (in particular those who are highly symptomatic or who are at high risk of tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy).

Medications used to control atrial flutter rate and/or rhythm include beta-blockers, sotalol, diltiazem, verapamil, digoxin, flecainide and amiodarone. Anticoagulation should be considered for all patients with atrial flutter, as with atrial fibrillation. The patient’s risk of thromboembolism (using a risk score such as CHA2DS2VASc) should be weighed against their bleeding risk (using a risk score such as HAS-BLED).

Q8. How do the most common medications used for atrial flutter work?

Flecainide (a class IC antidysrhythmic) produces a dose-related decrease in cardiac conduction time throughout the atrial myocardium. It should be used with atrioventricular (AV) blocking medications, as discussed above, to prevent the possibility of it slowing atrial flutter rate (e.g. from 300 bpm to 240 bpm) and thereby causing a paradoxical increased ventricular response (e.g. from 150 bpm in 2:1 block to 240 bpm in 1:1 conduction). It is contraindicated in patients with previous myocardial infarction or other significant structural heart disease. `

Amiodarone (a class III antidysrhythmic) blocks sodium channels, calcium channels, alpha and beta-adrenergic receptors, and prolongs the myocardial refractory period. It may also inhibit sinus node function and AV conduction. It has multiple significant non-cardiac side effects that are dose- and duration-dependent.

Sotalol (a class III antidysrhythmic) is also a non-cardiac-selective beta-adrenergic blocker. It may also prolong the QT interval, especially in predisposed individuals or in combination with other medications.

Metoprolol, propanalol and atenolol (class II antidysrhythmics) slow atrial rate via blocking beta 1 (the cardioselective) activity in the myocardium. They slow AV conduction and therefore increase the block without terminating the arrhythmia. They are often used in combination with other antiarrhythmics.

Diltiazem and verapamil (class IV antidysrhythmics) block calcium ion influx to cardiac smooth muscle and myocardium during depolarisation, hence reducing heart rate via conduction through the AV node. Again, these agents slow the ventricular rate but are not effective in restoring sinus rhythm.

Digoxin (a class V antidysrhythmic) is used mainly now only in patients with both heart failure and supraventricular tachycardias, if other medications and radiotherapy catheter ablation are contraindicated. Digoxin is a positive inotrope that has a vagomimetic effect, decreasing conduction through the AV and sinus nodes. It is less effective if there is high sympathetic activity.

Outcome

Jade’s resting and stress echo-cardiography tests were normal. She saw the cardiologist, who felt there was a low risk of embolisation, as she had a low CHA2DS2VASc score and low risk of recurrence if she complied with asthma preventer and minimised beta-agonist use. For this reason, she did not require anticoagulation. Jade did not want electrophysiological studies or radiofrequency ablation unless the episodes recurred. Because Jade has asthma, the cardiologist decided to treat her with flecainide 50 mg twice daily and diltiazem 180 mg daily instead of sotalol or other beta blockers. Several months later, Jade has not had a recurrence of atrial flutter. Annual Holter monitors are recommended to check for asymptomatic episodes of flutter or fibrillation. CT