Alcoholic cardiomyopathy

Jim, aged 67 years, had a stroke one year ago. He was admitted to hospital at the time under the care of a neurologist, but discharged himself against medical advice the next morning and was lost to follow up. Jim presented to a new GP complaining of increased shortness of breath over the past week, which had stopped him walking to the local shops 300 metres away. This was a particularly signi cant problem to Jim as he did not drive.

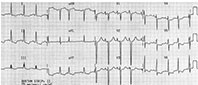

The GP noted that Jim smelt of alcohol, had mild foot and ankle oedema, a mildly raised jugulovenous pressure and decreased bibasal air entry on examination. Jim was not short of breath at rest, his blood pressure was 157/98 mmHg and his heart rate was 90 beats per minute and regular with occasional ectopics. He had grade 4/5 weakness of the right upper limb and a very mild facial droop that Jim said was from the stroke the year before. Jim was taking no medications. The GP took the opportunity to perform an ECG, which is shown in the Figure.

- The toxic effects of alcohol may cause supraventricular arrhythmias, sudden death, hypertensive heart disease and stroke. Acute, untreated alcohol withdrawal has been associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

- The prognosis for a patient with alcoholic cardiomyopathy depends largely on whether they can abstain completely from alcohol, how long they have been drinking and whether there are any other contributing causes of heart disease.

- There is now evidence against the routine implantation of automatic implantable cardiac de brillators for nonischaemic cardiomyopathy.

- The condition is termed ‘dry beriberi’ if the presentation is predominantly neurological.

- ‘Wet beriberi’ tends to signi cantly involve the heart.

- It is important that the affected patient have carefully administered treatment for beriberi. Cardiac complications may be worsened by the administration of thiamine due to consequent vasoconstriction and the inability of the damaged heart to cope with pumping against the increased arterial vascular pressure.

Q1. What does the ECG show?

The ECG shows evidence of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy with large precordial voltages and an LV strain pattern in leads with a dominant R wave (I, II and V6). There is also evidence of biatrial enlargement in lead V1 with a peak in the initial portion of the P wave followed by a deep terminal negative portion. The changes of right ventricular hypertrophy are masked by LV dominance; however, Jim had four-chamber dilatation on echocardiography.

Q2. What are Jim’s most likely diagnoses?

Jim is likely to be alcoholic and he is in mild biventricular failure. He may have alcoholic cardiomyopathy and, given his past history of cerebrovascular disease, he could also have myocardial ischaemia and/or diabetes. Thiamine deficiency is also an important consideration in alcoholics.

Q3. What is alcoholic cardiomyopathy?

Alcoholic cardiomyopathy is a clinical diagnosis made in a person who consumes excessive alcohol. There are often other signs, such as liver disease, parotid enlargement and hypertension (further damaging the myocardium), to support the diagnosis. Cardiomyopathy due to alcohol tends to be a type of dilated cardiomyopathy. There are many proposed causes of myocardial damage in alcoholic cardiomyopathy including metabolic effects (i.e. free radicals, effects on calcium and myofilaments, inhibited protein synthesis, fatty acid esterification), inflammatory effects, receptor abnormalities (e.g. beta 1-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors), activation of the renin–angiotensin system and coronary vasospasm.

The toxic effects of alcohol may cause supraventricular arrhythmias, sudden death, hypertensive heart disease and stroke. Acute, untreated alcohol withdrawal has been associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

There is now evidence against the routine implantation of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators into patients who have nonischaemic cardiomyopathy. Little effect has been shown on the long-term rate of death from any cause over routine medical care.1

The prognosis for a patient with alcoholic cardiomyopathy depends largely on whether they can abstain completely from alcohol, how long they have been drinking and whether there are any other contributing causes of heart disease. The patient can be reassured that their condition should improve if they have treatment for heart failure and abstain completely from alcohol.

Q4. What are the common ECG findings in alcoholic cardiomyopathy?

The common findings on an ECG from a patient with alcoholic cardiomyopathy are similar to those seen in patients with any diffuse cardiomyopathic process. Premature atrial contractions and supraventricular tachycardias are common, especially atrial fibrillation. Atrioventricular blocks, branch blocks and hemiblocks may also be seen. Pathological Q waves may be present in the absence of previous myocardial infarction. The ECG criteria for LV hypertrophy may be present.2 A prolonged PR and/or QT interval may also be noted. ST segment abnormalities and in particular nonspecific T wave changes, such as dimpling or cleaving of the T wave (especially well seen in lead I), have been described in alcoholic patients who continue to drink.1

Q5. What are the common findings on a cardiac echocardiogram in patients with alcoholic cardiomyopathy?

Alcoholic cardiomyopathy presents as a dilated cardiomyopathy and especially affects the left side of the heart. Therefore, left atrial and LV dilatation and enlargement, increased LV mass and reduced LV ejection fraction are most commonly seen. Biatrial dilatation and enlargement are also common. Both men and women tend to be equally affected but women may develop the condition with a lower chronic intake of alcohol.

Q6. What is beriberi and how is it related to alcoholic cardiomyopathy?

Beriberi is caused by a deficiency of thiamine pyrophosphate, the biologically active form of vitamin B1. This water-soluble vitamin acts as a coenzyme in the metabolism of carbohydrate and specifically in the formation of glucose. One month of low levels of this vitamin can cause a healthy person to develop signs of deficiency such as tachycardia, fatigue and reduced deep tendon reflexes.

The condition is termed ‘dry beriberi’ if the presentation is predominantly neurological, such as the development of peripheral neuropathy, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (altered mental state, ataxia, vomiting, ophthalmoplegia) or Korsakoff’s psychosis (progressive memory impairment, confabulation). This occurs typically in cases of low calorie intake.

‘Wet beriberi’ tends to significantly involve the heart. This chronic form begins with vasodilation and consequent high cardiac output, resulting in fluid retention due to activation of the renin–angiotensin system. The kidneys then retain salt to maintain intravascular volume, causing peripheral oedema. Congestive cardiac failure then results from the strain of maintaining the increasing stroke volume needed to supply blood to the organs.

Acute, fulminant beriberi is caused by a relatively sudden inability of the heart muscle to cope with this workload and is related to underlying disease of the myocardium, and vitamin and other dietary deficiencies. It results in peripheral cyanosis, hypotension, agitation, tachycardia and distended central veins, but peripheral oedema may be absent. There is a high mortality over hours to days if left untreated.

Q7. How is beriberi managed?

It is important that the affected patient receives carefully administered treatment for beriberi, and this may need to be arranged within the hospital system. Cardiac complications may be worsened by the administration of thiamine due to consequent vasoconstriction and the inability of the damaged heart to cope with pumping against the increased arterial vascular pressure, and this requires intensive monitoring. Significant psychiatric complications may worsen if the patient is allowed a higher calorie intake without co-administration of thiamine.

Hypoglycaemia must be treated if present, and thiamine should be parenterally administered in the first few days. Although it is a water-soluble vitamin, thiamine deficiency may still be possible in patients with severe or end-stage renal impairment.3 If the vitamin is given parenterally to such patients, it is possible to develop thiamine toxicity (irritability, weakness, headache, tachycardia), and so oral supplementation is preferred, 100 mg/day if required.

The following day, before further cardiac investigations could be performed, the hospital was once again forced to allow Jim to leave, and despite arrangements for follow up, Jim disappeared.

References

- Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1221-1230.

- Cadogan M, Nickson C. Life in the fast lane. Available online at: https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ecg-library/basics/left-ventricular-hypertrophy/ (accessed June 2017).

- Clase CM, Ki V, Holden RM. Water-soluble vitamins in people with low glomerular filtration rate or on dialysis: a review. Semin Dial 2013; 26: 546-567.

Further reading

Evans, W. The electrocardiogram of alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Br Heart J 1959; 21: 445-456. Nguyen-Khoa DT. Beriberi (thiamine deficiency). Medscape: 2017. Available online at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/116930-overview#a4 (accessed June 2017).