Cardio-oncology: the GP’s role

People with a history of cancer have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than the general population. Cardio-oncology, which covers the prevention, detection and treatment of CVD in people with cancer, is a growing field internationally, with important collaborative roles for GPs, oncologists and cardiologists in the care of patients before, during and after cancer therapy.

- Cancer and cardiovascular (CV) disease share many risk factors, and many cancer therapies are potentially cardiotoxic; patients with cancer have a greater risk of CV morbidity and mortality than the general population.

- Cardio-oncology encompasses the prevention, early detection and optimal treatment of CVD disease before, during and after cancer therapy.

- GPs can make an important contribution to CV risk assessment and management before and after cancer treatment.

- Although the role of GPs is increasingly recognised, it needs formalisation, with the development of appropriately funded care models.

- Enhanced multiway communication systems are key to ensure information is shared in a timely manner between specialists and GPs treating people with cancer.

Almost 1.1 million Australians were estimated to have a personal history of cancer in 2014, projected to rise to 1.9 million by 2040.1 Patients with cancer have a greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality than the general population, likely because of the many risk factors shared by CVD and cancer, the cardiotoxicity of many cancer therapies and factors related to the cancer itself.

Cardio-oncology is a growing field globally that encompasses the prevention, early detection and optimal treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD) during a patient’s cancer ‘journey’, as well as management of tumours of the heart.2,3 Optimal cardio-oncology care is multidisciplinary, with an important long-term role for GPs and primary care teams. Although this role is increasingly recognised, we believe it requires more formalised inclusion to provide cohesive, integrated collaborative care and improved patient outcomes.

This article reviews the relation between cancer and CVD and the latest guidance on cardio-oncology. It outlines the important role of GPs and primary care in cardio-oncology care of patients before, during and after cancer therapy.

Cancer and cardiovascular disease

More than a quarter (26%) of all deaths in Australia in 2018 were attributed to CVD.4 On average, patients with cancer have two to six times the CVD mortality risk of the general population. This increase in risk arises in the first year after diagnosis and persists for life.5 An Australian population-based study of 32,000 people with cancer found that CVD was the most common cause of death, and CVD deaths exceeded cancer cause-specific death by 13 years after the cancer diagnosis.6

The increased CVD risk among patients with cancer likely results at least partly from shared risk factors, combined with the cardiotoxic effects of many cancer therapies and the cancer itself. Risk factors shared by CVD and cancer include hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, drug and alcohol use, physical inactivity, heredity and nutritional factors.7

Cancer therapy and the cardiovascular system

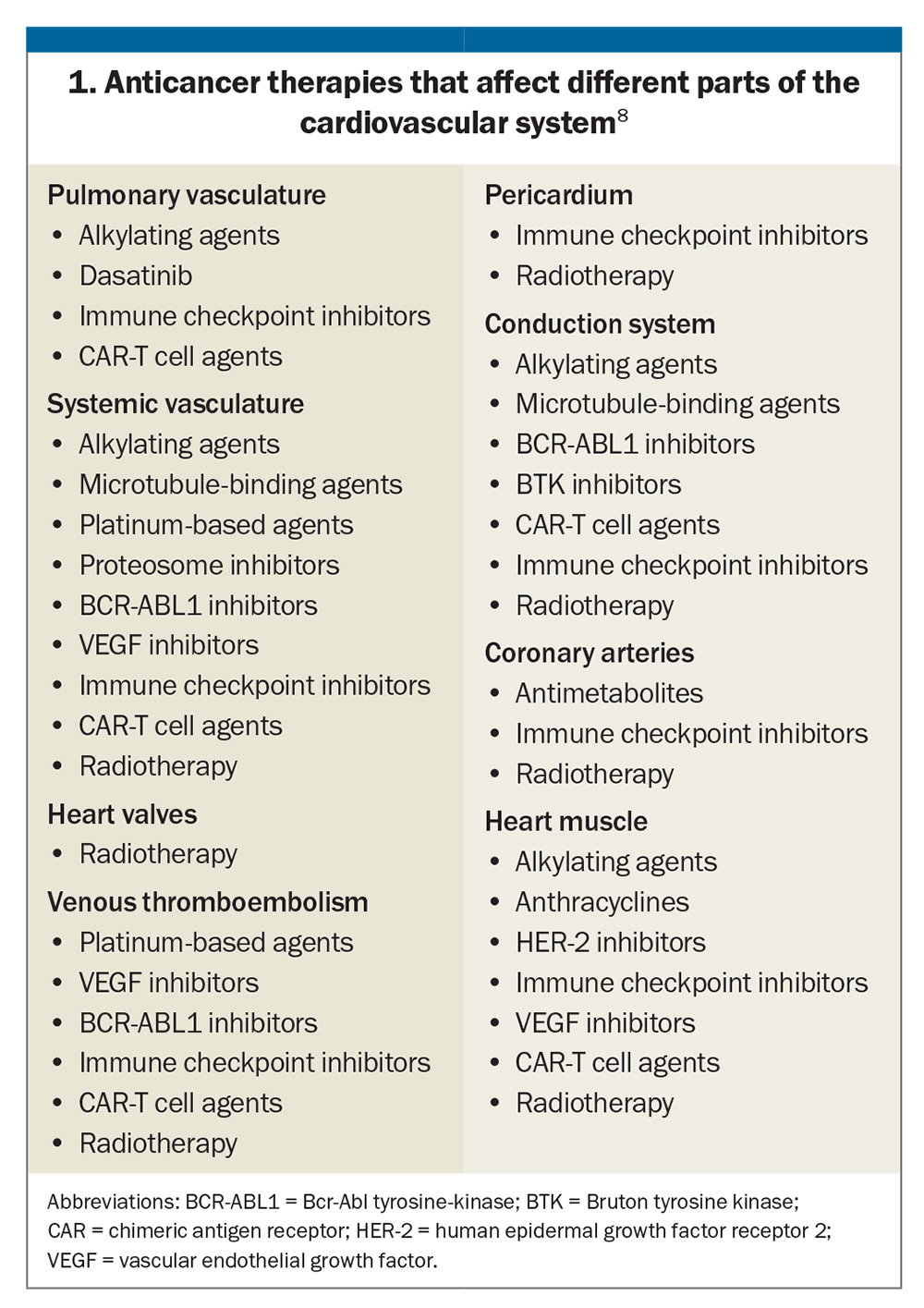

Almost all cancer therapies have been linked to cardiovascular effects, including conventional chemotherapy (e.g. anthracyclines, microtubule inhibitors, taxanes and platins), novel therapies (e.g. targeted biological therapies and immunotherapies) and chest radiation. Potential cardiovascular adverse effects may be acute or chronic and include hypertension, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, cardiac dysfunction, heart failure, myocarditis, valve disease, pericardial disease, thromboembolism, conduction defects and arrhythmias. There is also the potential for indirect cardiovascular toxicity through effects on the thyroid, adrenal glands, pituitary gland and pancreas.

Importantly, these adverse effects occur in both adult and paediatric populations. They are specific to the type of cancer treatment rather than the tumour type. The anticancer therapies that affect different parts of the cardiovascular system are shown in Box 1.8

Cardio-oncology guidelines

The first international guidelines on cardio-oncology were released in 2022 by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC; www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Cardio-oncology-guidelines).9 They are also available as a free downloadable app with a search function (www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Guidelines-derivative-products/ESC-Mobile-Pocket-Guidelines). Australian and New Zealand cardio-oncology recommendations for paediatric oncology patients were also recently developed by a Delphi consensus approach.10 Both documents are designed to aid consistency and standardisation of cardio-oncology care.

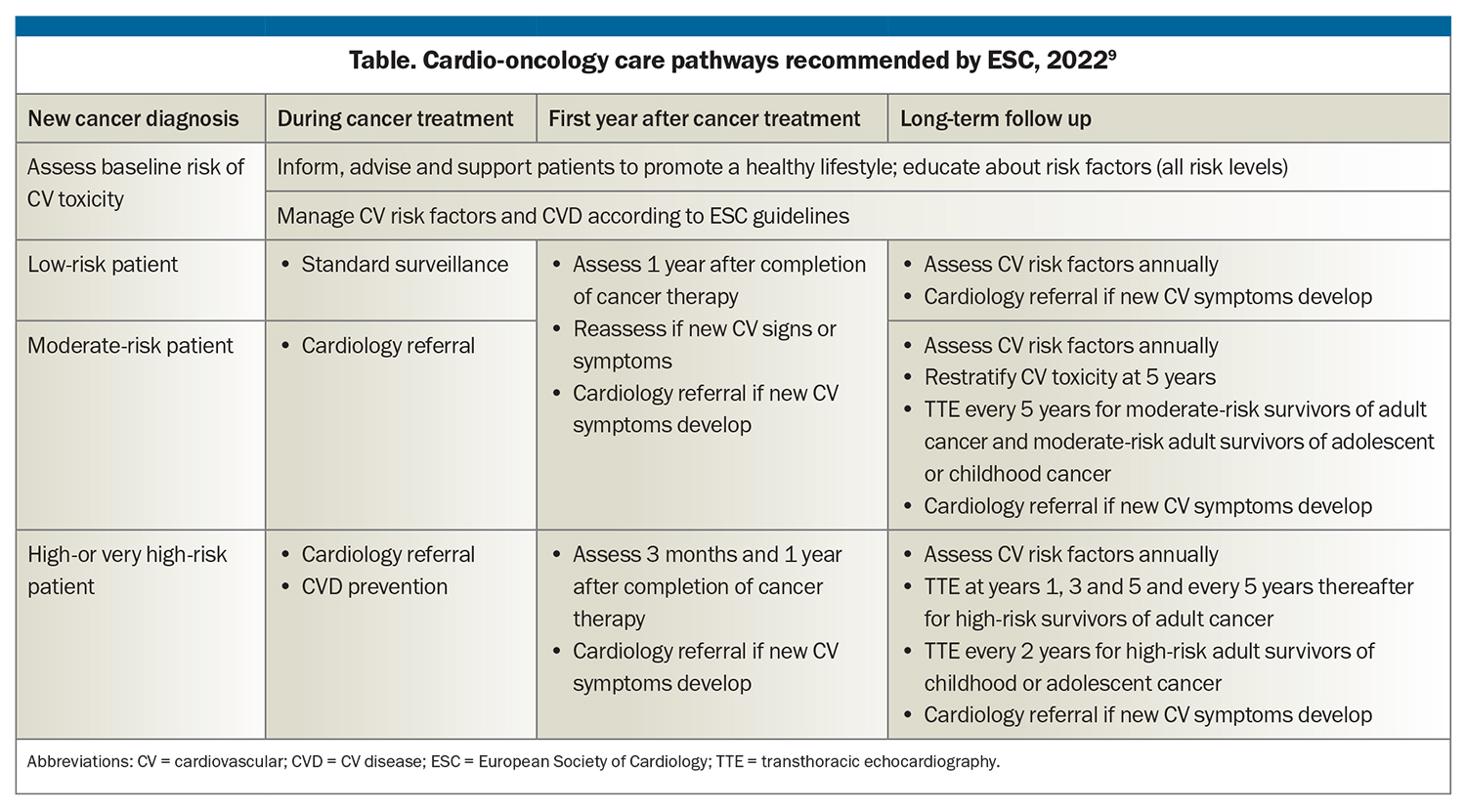

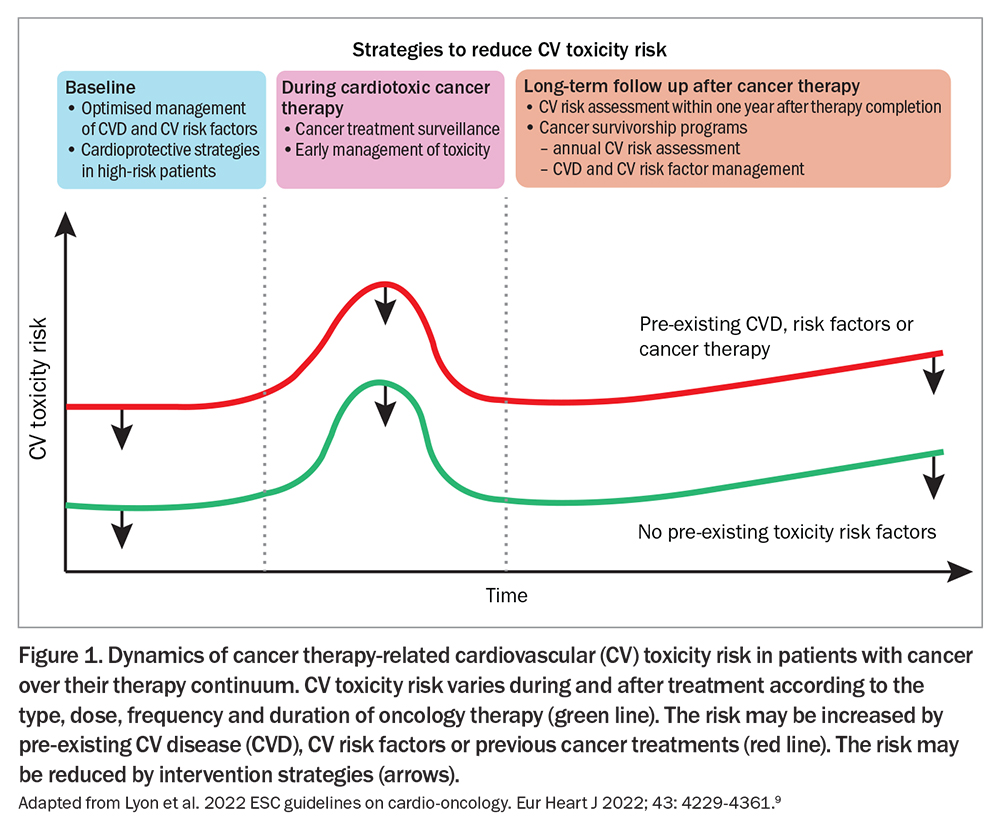

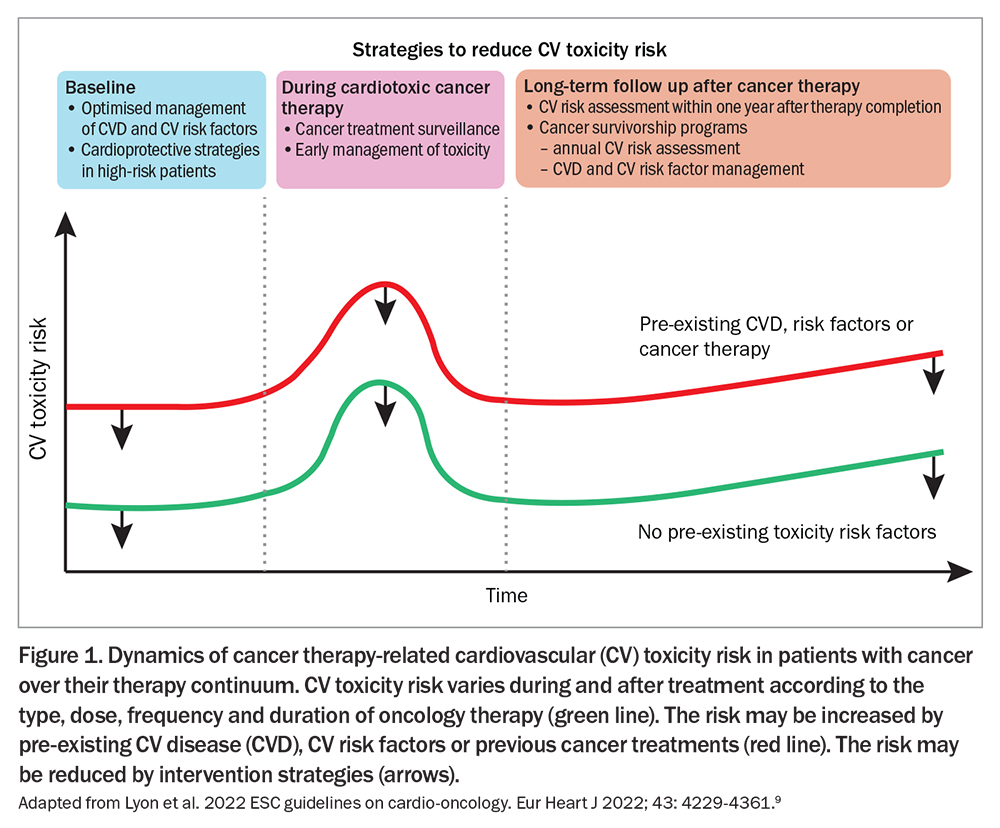

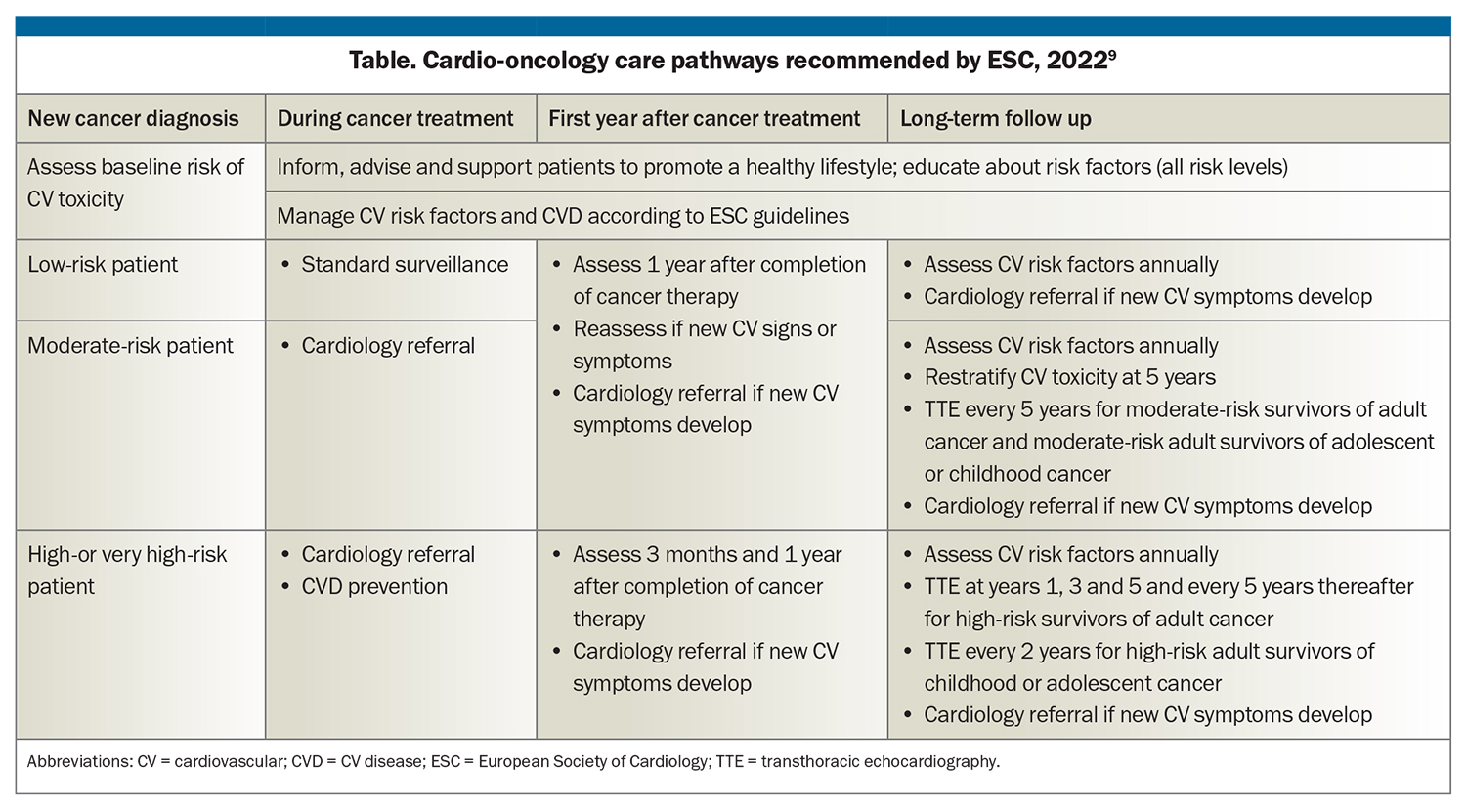

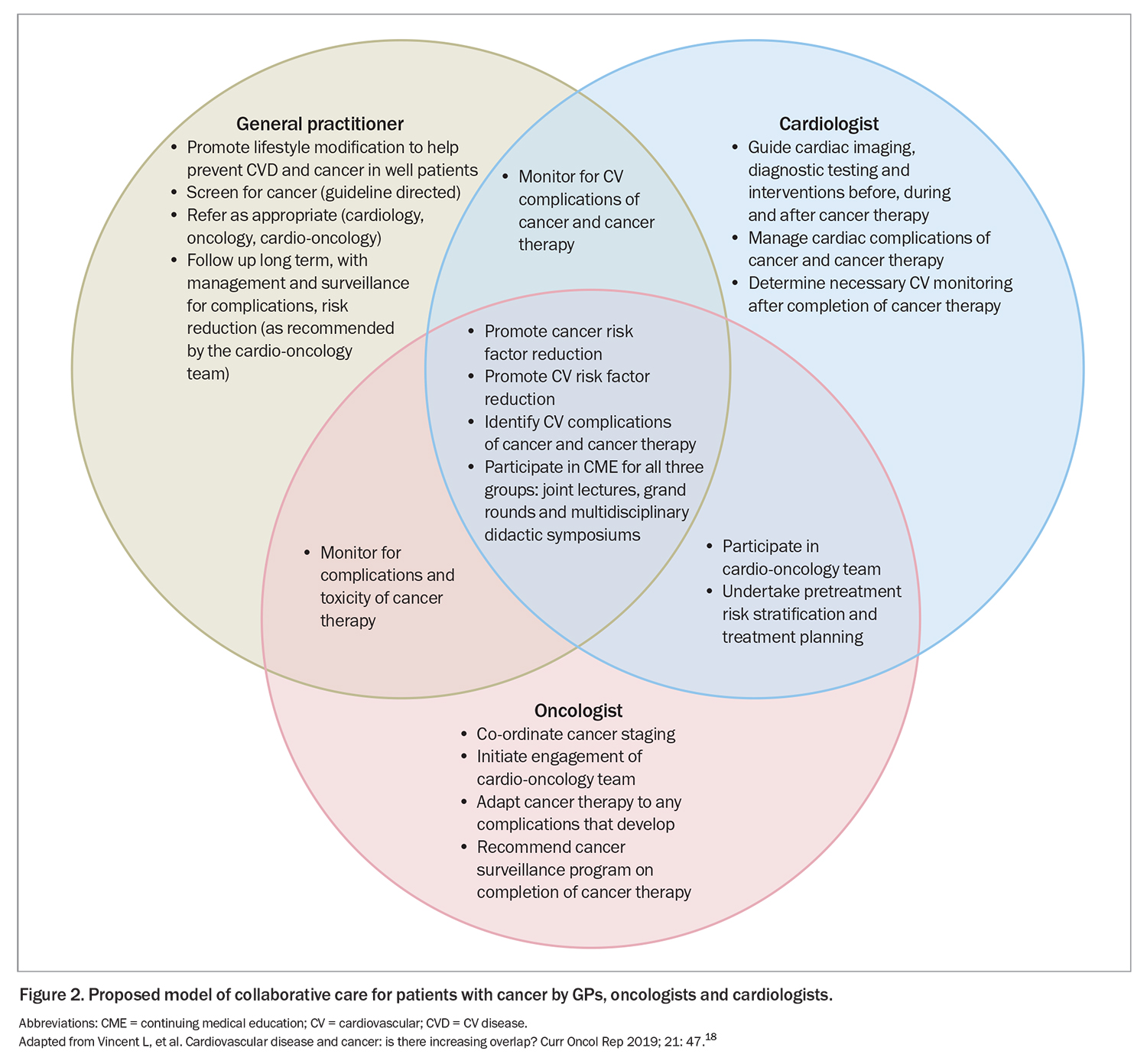

The aim of cardio-oncology is to provide personalised care that includes primary and secondary CVD prevention, CVD diagnosis and management, and surveillance for CVD in people with cancer. Optimal cardio-oncology care is patient-centred and supported by multidisciplinary care providers, including cardiologists, oncologists and haematologists, GPs, hospital and community nurses and allied health professionals. It is also pre-emptive, spans the entire cancer journey and varies according to the individual patient’s needs and risk profile (Table).9 Baseline risk stratification and management are a cornerstone and define the dynamics of care provision for the remainder of the patient’s journey (Figure 1).9

A prevention and surveillance plan for potential CVD complications is also recommended. This plan should include patient risk assessment, stratification and monitoring during treatment, other specific recommendations during treatment and on its completion, and surveillance, depending on individual circumstances.9

Importance of the GP’s role

As increasingly recognised, a key component of successful implementation of the cardio-oncology guidelines and recommendations is care integration. Primary care is mentioned in the ESC guidelines, but we believe its role requires greater acknowledgement and delineation to support true collaborative care.3 This need was also highlighted in a recent editorial by health professionals working in cardio-oncology in Australia.11

Cancer care requires a ‘care continuum’, and primary care has a role across each phase of the cancer journey. Primary care has community cultural links, which are important for optimal long-term care, especially for culturally and linguistically diverse populations. GPs can integrate care for cancer survivors, utilising their skills in chronic disease management, health promotion and lifestyle modification.12 GPs have insights into the psychosocial situation of their patients and can provide holistic care and oversight. Further, GPs and primary care are key to providing local supportive care for patients in regional, rural and remote areas, where access to specialist care may be limited.13

Consequently, it is crucial that primary care providers, GPs and nurses are acknowledged as key members of the multidisciplinary cardio-oncology team and that effective multiway communication systems are established to support cohesive collaborative care. Oncology and cardiology specialists are recommended to ensure timely multiway communication with the patient’s GP to keep them up to date with the management and surveillance plan and to emphasise to patients the importance of having a regular GP who is a member of the overall care team. Nurse practitioners and community nurses may also have an important role; in some locations, they may be a patient’s initial and main health contact in the community.

The Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA) and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ) have been working jointly since 2021 to address CVD in patients with cancer. The working group recently outlined some of the challenges in improving CVD outcomes in people with cancer in Australia and priority areas for improvement.14 Formalised cancer and cardio-oncology pathways will enable and support high-level standardised care and prevent fragmentation of care. Ideally, more formalised pathways could also support the establishment of care models that include GPs, with associated appropriate Medicare funding. With such frameworks, GPs are likely to prove invaluable support for other cardio-oncology team members, especially in primary and secondary prevention, while also maintaining a centralised primary care holistic approach.

COSA and CSANZ are also developing educational resources for health professionals and patients. There is the potential to develop guidelines, recommendations and resources more specific to the Australian context that could fully incorporate the role of GPs and primary care.

The GP’s role: before cancer treatment

Prehabilitation

GPs have a key role in patient prehabilitation before treatment for cancer. This includes providing the best possible management of pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes; encouraging a healthy lifestyle, including exercise, nutrition and smoking or vaping cessation; and allied health referrals as indicated. It may involve the introduction of protective medications, such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and statins, under the guidance of cardio-oncology or cardiology treating teams as needed.

Risk stratification

GPs also have an important role in providing information to treating oncologists and cardiologists about the patient’s cardiovascular health. If more background information is available to these specialists before cancer treatment, then more optimal decisions regarding treatment and monitoring can be made.

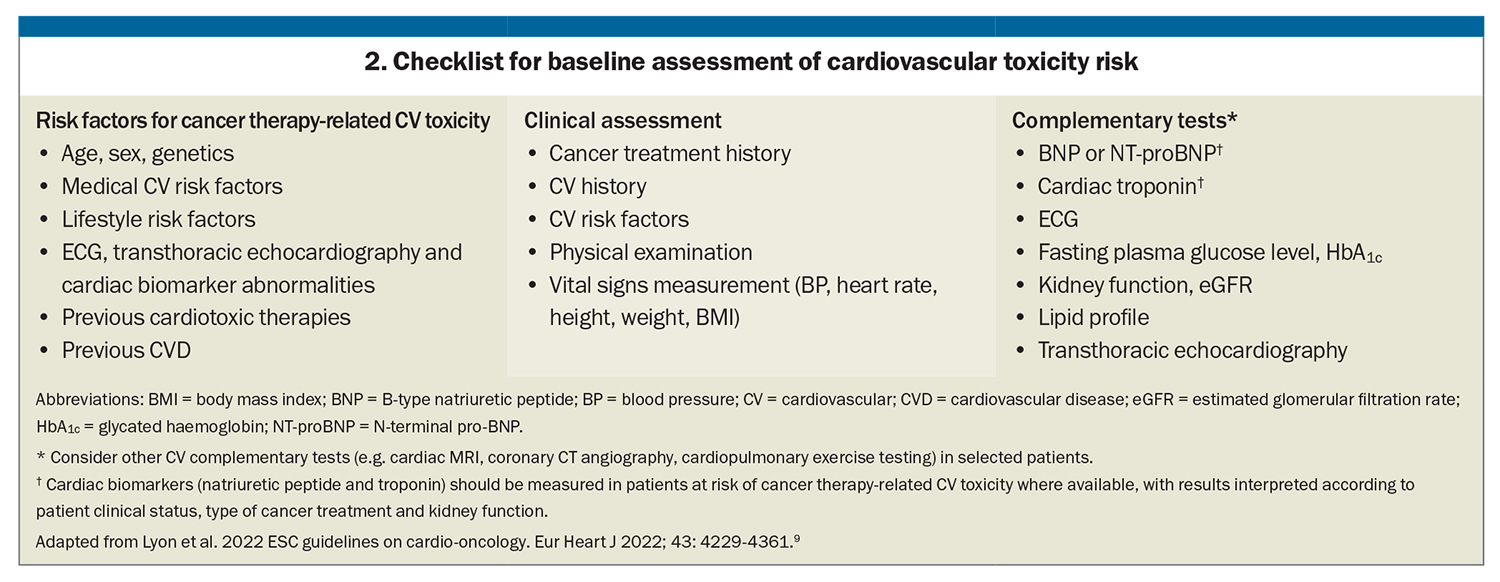

It is imperative to identify high-risk patients before treatment begins. Risk stratification is based on pre-treatment risk assessment and the potential risk of the proposed treatment. A suggested checklist for assessing the patient’s baseline cardiovascular toxicity risk is shown in Box 2.9 Detailed risk stratification and proformas are provided in a dedicated publication.15 They are also available via an app (www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Guidelines-derivative-products/ESC-Mobile-Pocket-Guidelines).

GPs can assist with risk stratification by helping complete baseline cardiovascular risk assessment.9 Key information for pre-treatment cardiovascular risk assessment that needs to be communicated to treating oncology and cardiology teams includes:

- CVD risk scores – of note, at the time of writing, the newly released AusCVD risk calculator (www.cvdcheck.org.au) does not include a history of cancer treatment as a risk factor, so clinical interpretation is advised

- results of cardiovascular investigations, including ECGs, echocardiograms, CT calcium score

- history, including CVD, cardiovascular risk factors, thromboembolism and previous potentially cardiotoxic cancer treatments

- family history

- comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, chronic kidney disease) and concurrent medications

- waist circumference and body mass index (BMI)

- lifestyle factors (exercise, nutrition, smoking, vaping, current or history of alcohol or illicit drug use).

Psychosocial support

GPs are well experienced in providing psychological support to their patients. This can include primary care supportive counselling and psychology referrals, as well as information about resources for patients and carers, such as the Cancer Council, Canteen, specific support groups and disease-specific foundations.

The GP’s role: during cancer treatment

During the active cancer treatment phase, GPs can provide supportive care to the patient as needed and be involved in multiway communication with tertiary care providers. Cardiovascular toxicity is dynamic (Figure 1), and it is important for GPs to support continued risk minimisation and management, whether through encouraging lifestyle changes, supportive counselling or medication.

The detailed monitoring and investigations recommended during cancer treatment are usually overseen by oncologists and cardiologists. These include echocardiography with myocardial global longitudinal strain (GLS) assessment, measurement of cardiac biomarkers (cardiac troponin, B-type natriuretic peptide) and advanced cardiac imaging. There are also specific indications for the commencement of cardioprotective medications such as ACE inhibitors or ARBs, beta blockers, statins and antiplatelet therapies. Ideally, the cardio-oncology team will continue to update the GP about the management plan along the treatment journey. Establishing a bidirectional communication pathway between involved health professionals will allow for cohesive and optimal holistic patient care.

The GP’s role: after cancer treatment

After cancer treatment, cancer survivors require awareness and monitoring for cancer- and treatment-related risk factors and adverse effects. GPs and primary care teams can expect to be provided with a long-term follow-up plan and surveillance guidelines for late effects. If these are not provided, we recommend the GP or primary care team request such a plan from the cardio-oncology team to ensure long-term follow-up is appropriate and clearly communicated to all health professionals and to the patient. A surveillance plan is especially important for paediatric patients, who will at some stage transition to adult care settings (Table).9

GPs are well placed to oversee long-term surveillance and to support and promote risk factor reduction and health improvement measures. This includes monitoring blood pressure and liver and renal function, counselling about nutrition, exercise and substance use, supporting mental health, refining medication and referring back to the cardio-oncology team as indicated.

Rehabilitation is paramount after any cardiac event and should proceed as per local guidelines, ensuring all key health team members are informed. There is strong evidence that cancer patients and survivors are underprescribed medications for conventional cardiovascular indications such as aspirin and statins.16 This in turn leads to increased cardiovascular admissions among cancer patients and survivors.17 For patients with diabetes, some novel antidiabetic drugs such as SGLT2i and GLP-1 antagonists have been found to have cardiovascular benefits, so having related specialist input and consideration by GPs, if indicated, could prove beneficial.

Ensuring the GP and primary care are involved after cancer treatment is a crucial component of recommended cardio-oncology long-term care and surveillance. A proposed model of collaborative care by GPs, cardiologists and oncologists within a cardio-oncology team is shown in Figure 2, including specialty-specific roles and interdisciplinary overlap.18

Communication with patients

It is important that patients with cancer are made aware of the shared risk factors between cancer and CVD and their own personal surveillance plan to minimise potential short- and long-term risk. A patient communication document is available to accompany the ESC guidelines; this is well designed, albeit with some limitations because of variable health literacy and cultural and linguistic diversity.19

Along the cancer journey, health professionals are recommended to communicate regularly and clearly with patients and to provide education, support and counselling as indicated. This open communication should continue in the primary-care setting, where patients can be supported and empowered to make optimal lifestyle choices as well as informed of the signs and symptoms that indicate the need for medical review. It is also paramount that patients understand potential short- and long-term treatments and recommendations, which is likely to improve adherence. Education resources and digital health tools available through ESC and local hospital and treating centres can also be used to aid patient knowledge and self-care.

Conclusion

Clearer role definitions, awareness and improved multiway communication are key to minimising fragmentation of care and to providing optimal cardio-oncology care to our patients. Risk management and monitoring are crucial long-term elements of cardio-oncology care. Enhanced awareness and education about cardio-oncology and the important role of GPs and primary care could be addressed through professional organisations and networks for GPs, primary care, oncology and cardiology. More standardised and formalised care models that include the important role of GPs might also help support appropriate funding for such care provision.

Optimal cardio-oncology care will hypothetically lead to fewer hospital admissions and reduced cost to health budgets, while improving long-term quality of life of cancer patients. Cardio-oncology initiatives, frameworks and pathways need to include GPs and primary care, acknowledging their generalist skills across a lifespan and their important role over the cardio-oncology trajectory. CT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Cancer Council Australia. Number of Australians living with or beyond cancer to surge 72% by 2040: 1 in 18 Australians will have a personal history of cancer [media release]. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia; 2018. Available online at: https://www.cancer.org.au/media-releases/2018/number-of-australians-living-with-or-beyond-cancer-to-surge (accessed September 2023).

2. Brown SA. Preventive cardio-oncology: the time has come. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020; 6: 187.

3. Cehic DA, Sverdlov AL, Koczwara B, Emery J, Ngo DTM, Thornton-Benko E. The importance of primary care in cardio-oncology. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2021; 22: 107.

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National mortality database. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/our-data-collections/national-mortality-database (accessed September 2023).

5. Ye Y, Otahal P, Marwick TH, Wills KE, Neil AL, Ven AJ. Cardiovascular and other competing causes of death among patients with cancer from 2006 to 2015: an Australian population-based study. Cancer 2019; 125; 442-452.

6. Koczwara B, Meng R, Miller MD, et al. Late mortality in people with cancer: a population-based Australian study. Med J Aust 2020; 214: 318-323.

7. Blaes AH, Shenoy C. Is it time to include cancer in cardiovascular risk prediction tools? Lancet 2019; 394: 986-988.

8. Ferreira VV, Ghosh AK. Essentials of cardio-oncology. Clin Med (Lond) 2023; 23: 52-55.

9. Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J 2022; 43: 4229-4361. Erratum in: Eur Heart J 2023; 44: 1621.

10. Toro C, Felmingham B, Jessop S, et al. Cardio-oncology recommendations for pediatric oncology patients. An Australian and New Zealand Delphi consensus. JACC Adv 2022; 1: 1-16.

11. Nolan MT, Creati L, Koczwara B, et al. First ESC cardio-oncology guidelines: a big leap forward for an emerging specialty. Heart Lung Circ 2022; 31: 1563-1567.

12. Jefford M, Koczwara B, Emery J, Thornton-Benko E, Vardy JL. The important role of general practice in the care of cancer survivors. Aust J Gen Pract 2020; 49: 289-292.

13. Williams TD, Kaur A, Warner T, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes of cancer patients in rural Australia. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023; 10: 1144240.

14. Sverdlov AL, Koczwara B, Cehic DA, Clark RA, Hunt L, Nicholls SJ, Thomas L, Thornton-Benko E, Kritharides L; Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA)–Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ) Cardio-Oncology Working Group. When cancer and cardiovascular disease intersect: the challenge and the opportunity of cardio-oncology. Heart Lung Circ 2023 Jun 13: S1443-9506(23)00510-3. Epub ahead of print.

15. Lyon AR, Dent S, Stanway S, et al. Baseline cardiovascular risk assessment in cancer patients scheduled to receive cardiotoxic cancer therapies: a position statement and new risk assessment tools from the Cardio‐Oncology Study Group of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology in collaboration with the International Cardio‐Oncology Society. Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22: 1945-1960.

16. Untaru R, Chen D, Kelly C, et al. Suboptimal use of cardioprotective medications in patients with a history of cancer. JACC Cardio Oncol 2020; 2: 312-315.

17. Ngo DTM, Williams T, Horder S, et al. Factors associated with adverse cardiovascular events in cancer patients treated with bevacizumab. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 2664.

18. Vincent L, Leedy D, Masri SC, Cheng RK. Cardiovascular disease and cancer: is there increasing overlap? Curr Oncol Rep 2019; 21: 47.

19. Asteggiano R, Dent S, Farmakis D, et al. ESC clinical practice guidelines on cardio-oncology: what patients need to know. European Society of Cardiology; 2022. Available online at: https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Guidelines/Documents/ESC%20Patient%20Guidelines%20Cardio%20Oncology%20-%20final.pdf (accessed September 2023).